Eighth-graders, from right, Caroline Huber, Lottie Dubert, Jessica Alewine and Neha Bhat work on building a polynomial roller coaster with graham crackers, marshmallows and toothpicks during their algebra 2/trigonometry class at Nysmith School for the Gifted in Herndon, Va. (Photo by Lexey Swall/GRAIN for The Washington Post)

It’s 8 a.m. as the yellow buses begin to roll up, bouncing with kids, and Carole Nysmith pushes open a heavy glass door. Under a late autumn sky, the 79-year-old educator wraps her coat tightly around her and takes up her regular spot in front of the glass-walled schoolhouse she built for them, the Nysmith School for the Gifted. Out in the parking lot, a woman slides open the back of her SUV to herd two boys, hurriedly stuffing their collared shirts into the required khaki pants. A father wearing Air Force camouflage holds his primary-school-age daughter’s hand and asks, “Got everything?”

Nysmith follows the mix of elementary- and middle-schoolers into the sun-washed foyer, and watches them stream down hallways filled with their chatter. In between hugs for the younger ones, Nysmith calls out, “Good morning, Caroline. Hello, Sammie. Hi, Zane. Have a wonderful day, Veda.”

“Hi, Miss Ny,” says a tiny girl shuffling under an enormous purple backpack.

The staff affectionately refers to the school’s founder as their “wandering grandmother.” She is still involved in administrative affairs, gives tours to prospective families and helps students in the Media Center, but handed off the day-to-day running of the school seven years ago to her older son, Kenneth Nysmith. The 53-year-old father of three, who goes by Ken, towers over his mother but wears the same amused smile as he strides down the hallways in a crisp green dress shirt and Star Wars-themed tie (Obi-Wan Kenobi from Episode 1), calling out to students by name. Every Nysmith teacher wears an ID lanyard, most of them sporting pins that each represent five years of employment; the average tenure is over 10 years. Ken’s badge reflects the fact that he has been at the school almost since it opened 32 years ago.

“My mom was a teacher and sort of had this crazy little idea for Fairfax County’s [gifted and talented] program. She saw a need for kindergarten through second grade … children who are too young to join the program and get them interested in academics early,” he says. “It grew from there.”

The school, relocated from Reston to Herndon, Va., in 2000, serves more than 600 kids, from preschool through eighth grade. As Ken Nysmith ushers a visitor into a gym with a rock-climbing wall, he says, “We’re noisy, but you’ll notice I’m not the bogeyman as we walk around.”

Backpacks lie in a heap in the hallway. Cellphones and iPads are visible, but he says theft has never been a problem.

“We don’t have a lot of discipline problems, because the kids want to be here. That’s not to say we’re perfect. We’re all human and learning to get along, but it’s beautiful.”

If the sales pitch feels a bit heavy-handed, it could be because the headmaster is keenly aware of the question that most new visitors walk in with: What’s so special about the place anyway?

On paper, Nysmith excels at the kind of metrics that make tiger parents purr. Its students regularly place in the top 1 percent nationwide in national tests for math, reading and language. The most recent Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth report included Nysmith as one of the Top 10 Schools in the World, and honored 27 Nysmith second- to eighth-graders for achieving highest honors in its above-grade-level testing. The school website’s list of high schools that graduates often go to include Sidwell Friends, Potomac School and Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology.

Those results are impressive even for an institution that can choose its students. So how has Nysmith managed to do all this? Some education experts cite selectivity built into the very notion of giftedness. There’s also self-selection in the form of highly motivated parents willing to foot the average annual tuition of $28,440 (although the school offers some financial assistance). The school’s boosters are more likely to stress a rigorous curriculum and nurturing environment filled with people who “get” their students.

“Gifted children are different. They have different needs,” Ken Nysmith says.

“Traditionally they’re less mature, although intellectually they may be thinking a year or two beyond. Sometimes they are perfectionists, and some of it is helping them find that balance of ‘Where do you stop?’ That’s a challenge for these children. They want to know ‘Why am I different?’ They don’t have that sense of being normal because they’re thinking in a different plane.”

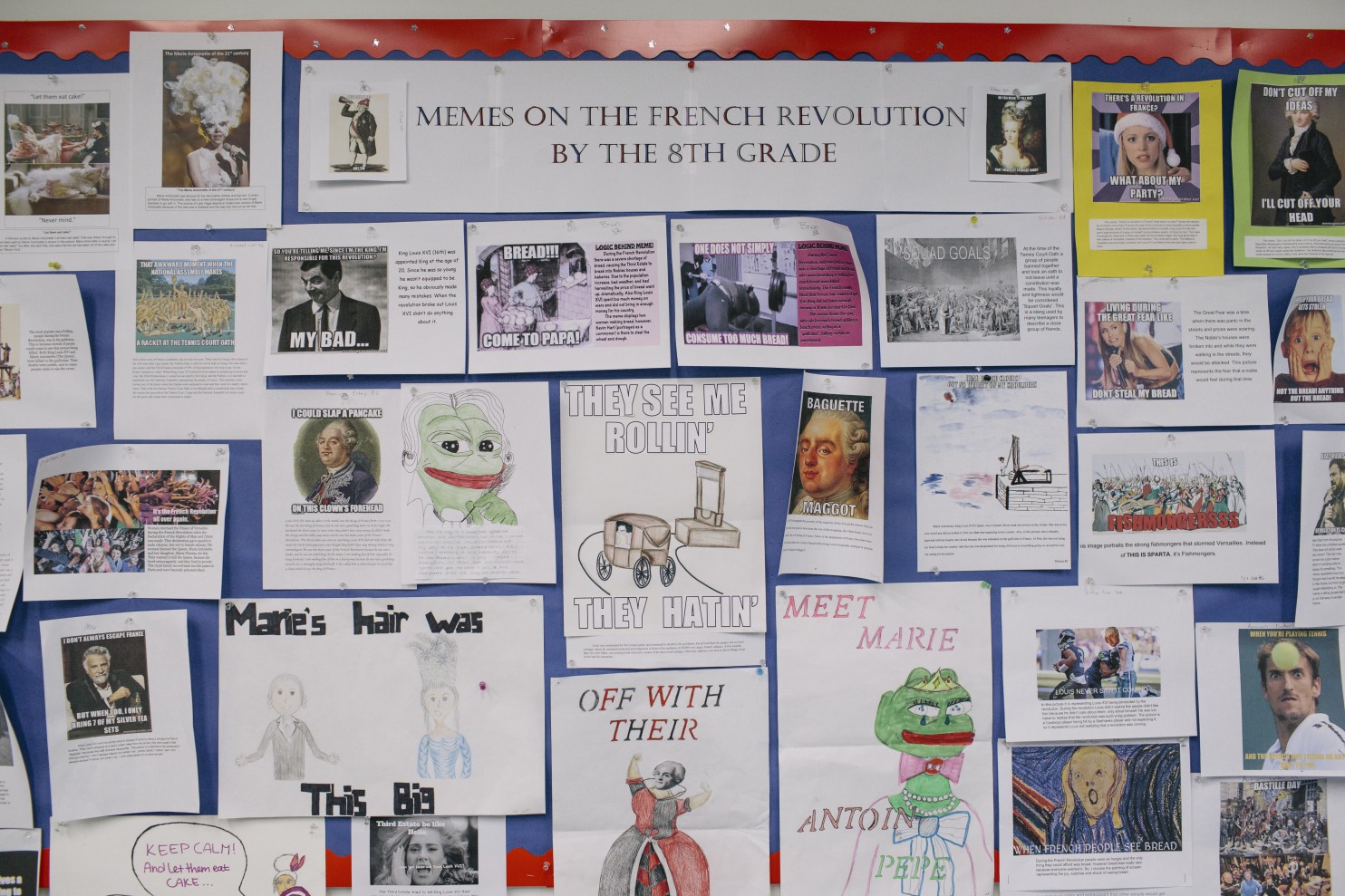

Students use pop culture to illustrate history on a bulletin board at Nysmith. The school opened in 1983 with 55 children, they now teach more than 600 students ranging from pre-K to eighth grade. (Photo by Lexey Swall/GRAIN for The Washington Post)

The idea of gifted education has long been controversial. In the early 20th century, studies of giftedness “evolved from research on mental inheritance” and “subnormal children,” according to a history of the field on the website of the National Association for Gifted Children, a Washington organization made up of educators, academics and parents that advocates for gifted education.

The Cold War — and in particular the launch of Sputnik in the late 1950s — lent a sense of geopolitical urgency to identifying little brainiacs. The federal government in the early 1970s “brought the plight of gifted school children back into the spotlight,” the association’s history says. The definition of giftedness expanded over the years, along with programming options. But cries of racial and economic exclusion have dogged the endeavor. (Whites and Asians tend to be overrepresented in gifted and talented programs, federal data show.)

The criteria are not consistent, say critics such as consultant Andrew Rotherham, who has argued that the value of the gifted label has more to do with scarcity.

Yet such criticisms have failed to sway parents and educators who insist that without such programs, schools not only shortchange exceptionally bright kids, but can discourage them.

During her 15 years teaching in Fairfax County public schools, Carole Nysmith says she noticed a shortfall in challenging classes for children with advanced intellectual abilities, so she came up with a strategy to teach kids “turned off by education” because they were being taught things they already knew. She later decided to take her methods private and in 1983, after pulling together money from a family inheritance, the sale of a beach house and a line of credit, she started the Nysmith School for the Gifted in the old Reston Visitors Center. Focused on accelerated science and technology programs in small classes with a 9 to 1 student-teacher ratio, the school opened with more than 50 kids.

Today, Nysmith’s annual tuition ranges from $23,000 for full-day preschool to $33,880 by eighth grade. A quarter to a third of families receive financial assistance, up to half the annual tuition.

“We’ve got a whole spectrum of economic backgrounds, ethnic backgrounds. As you watch the children in the halls, we’re a very diverse community,” Ken Nysmith says.

A more specific breakdown is not available, despite frequent requests by prospective parents, says admissions director Marian White.

“People will call and say, what percentage do you have of African American or whatever, and they’ll go down the list. Well, we don’t break it down that way,” she says, although the school says its students represent 55 countries and the U.S. military. “It doesn’t matter male or female, it doesn’t matter what ethnicity. It doesn’t matter to us, so we don’t even track it. Because what matters is if this program and that child are a really good fit.”

Carole Nysmith is greeted by students as they arrive, as headmaster Ken Nysmith looks on. Carole Nysmith encourages all students to greet her in the morning with eye contact. (Photo by Lexey Swall/GRAIN for The Washington Post)

Parents have been known to quit their jobs, sell their homes, just to move to the area and send their kids to Nysmith. They come, Ken Nysmith says, for the school’s “common sense” approach to teaching: “We teach the children what they’re ready to learn. When people ask, What is our goal? Is it test scores, is it a certain number of kids getting into TJ — no. It’s really, Do the children love to learn?”

Cindy Wimmer, a McLean, Va., jewelry designer, says that philosophy is what led her and her husband to send all four of their children to Nysmith: Gabriel and Collin, who graduated and now attend public schools, and Chandler and Nathaniel, who are still at Nysmith.

The three younger boys are with her as she slogs through rush-hour traffic on a brisk November afternoon. She pulls her SUV into the parking lot of the Fencing Sports Academy in Fairfax, and the boys jump out while their Scottie puppy, McGregor, settles down in the back seat for a quiet snooze. Once inside the fencing club, the boys go through a warm-up routine of quick turns and lunges to prepare for the advance, retreat and balance drills. Then they strap on their white jackets and protective masks.

Wimmer keeps an eye out for her husband, Randy, who is on his way from the federal government contracting company he owns in Tysons Corner. When he turns up, he explains private school had not been a given. The 47-year-old Navy veteran was one of seven kids in a blue-collar family in southwestern Virginia and the first to graduate from college.

“I was not a good student,” he says. So he was blindsided by firstborn Gabriel’s high IQ test scores. After watching the boy tear through primary-level books in kindergarten, Randy Wimmer remembers thinking, “Wow, where did that come from?”

Gabriel, now 15, has a keen interest in cybersecurity defense strategies. He attends Thomas Jefferson, where the largest group of Nysmith graduates go each year. (About 2,800 kids applied to join the class of 2019 at TJ; just under 500 were accepted.) His younger brothers are also precocious but in different ways.

Thirteen-year-old Collin is an outgoing creative writer who makes fanciful origami shapes with his eyes shut. He is now in an advanced placement program at Longfellow Middle School, his neighborhood school. As the foils clash in the background at the fencing club, Collin talks about how he likes to “do stuff that involves hand-to-eye coordination, like tying Celtic knots or globe knots or monkey fists.”

Redheaded Chandler, 11, is entrepreneurial like his dad. In September he placed second in a toy competition held by a local museum and Hexbugs with his model toy, a device named Maneuver. “It was a game of checkers on a Rubik’s Cube sort of thing, three-dimensional,” says the sixth-grader. “Hexbugs may actually market it, but if they don’t there are a lot of Kickstarter ideas, so I’d like to do one of those.”

Nathaniel, the youngest, is a builder. His father claims he could assemble complex Lego structures before he could walk. “It’s so easy,” the first-grader says, “that I decided to make a castle bigger than my head. Much bigger.”

He jumps on his brother Collin’s back and tosses an arm around Chandler. All three of them are shiny with sweat.

Randy and Cindy Wimmer don’t see themselves as hard-driving, Type A parents, nor do they come off that way. Cindy says her family’s experience at Nysmith shows there’s no one-size-fits-all education. Asked about the hefty price tag for private school for four kids on a springboard to even more expensive colleges, Randy pauses a moment to exhale.

“I know exactly what I’m going to be doing the day I die — still paying for college loans,” he says, only half joking. “But my wife and I decided, we’re blessed with these kids, we have the means, let’s invest it in their education.”

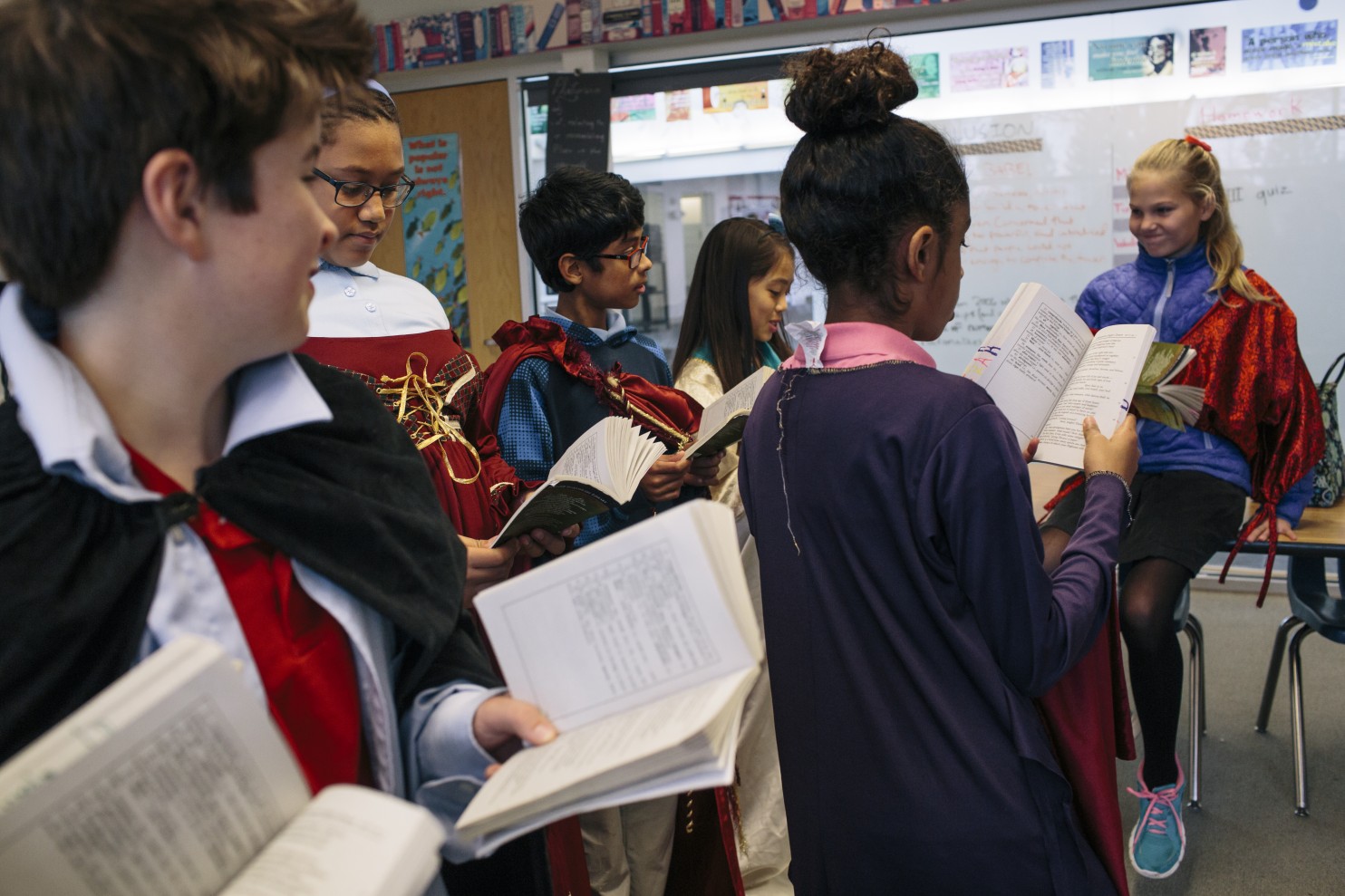

Students in a sixth-grade language arts class act out Shakerspeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” (Photo by Lexey Swall/GRAIN for The Washington Post)

“Once more unto the breach!”

It’s 10:15 on a Wednesday morning and language arts teacher Philip Stephens is taking his students through Shakespeare’s “Henry V.” When he challenges his seventh-grade students to sum up the play in 20 seconds, hands shoot up.

“So there’s this English king guy, Henry … and the French dauphin thinks Henry’s a joke, so Henry declares war on France.”

“Good! And what is a breach?” Stephens asks.

“A gap in a wall,” says a previously silent boy, tugging at the pulp of the tangerine splayed out on his desk.

“Awesome,” says Stephens.

In his class, as with most classes at Nysmith, there may be students learning at different grade levels. Two teachers in every classroom allow for such “diversification,” a term Nysmith defines as teaching to four grade levels within a class for accelerated instruction in reading, math, science, logic and foreign languages. In other words, if a third-grader is ready for fifth-grade work, she gets to work at that level without leaving her peers.

To determine whether a kid is ready for accelerated learning, White says, intellectual assessments are given in first grade.

“Because we diversify, sometimes parents get caught up in the idea that that’s the goal and they push their children,” Ken Nysmith says, “whereas we believe in nurturing them. We nurture them at the next level if we think they are going to be successful, but when a child feels pressure, it’s counterproductive. That’s sometimes the hardest part of my job, saying to a parent, ‘You know, your child’s just not ready for it.’ ”

For a school that prides itself on preparing kids to thrive in intensely competitive environments, it may seem odd for the headmaster to sound so allergic to academic pressure. But it’s a key tenet of the school’s approach. In a post about report cards on the school’s website, he pleads with parents “not to stress to their child that they must make straight A’s.” “The psychological damage that can be done to young children is profound,” he writes. “Is that grade worth having your child hate the subject or you, or hate themselves, for the rest of their lives?”

“We grade on effort,” Nysmith says. “Our view is that grades are motivational; they are a tool to inspire children to do their best; they are not a goal.”

Parents are not the source of pressure all of the time, says 2003 Nysmith alum Jonathan Chang, who recalls there were always kids who felt a need to excel, including himself.

“My brother is profoundly autistic and can’t speak, and I just put a lot of that pressure on myself to not give my parents something else to worry about,” says the 27-year-old. “I never really rebelled in any terrible way. I spiked my hair? That was pretty much as far as it went.” But he credits the school’s supportive, close-knit environment for opening up a naturally shy kid and giving him the confidence to veer from his natural strengths in science and math. After taking a class with Stephens, he fell in love with literature and now teaches English at a private high school in Oakton, Va.

“There are those days, of course, where I think it would’ve been so much fun to have become a software developer or an engineer of some kind,” Chang says. “But I don’t regret having become a teacher, because there’s something very different about affecting a young person’s life the way Mr. Stephens affected mine. I guess that’s what nine years of Nysmith will do to you.”

Eighth-graders Megan Wenig, from left, Grace Morgan, Gabrielle Byas, Anna Blasdell, Kirthi Kumar, Neha Bhat and Ethan Bean spend lunch together in the sunny lounge in the Upper School, a privileged spot, reserved for eighth-graders to relax and hangout. (Photo by Lexey Swall/GRAIN for The Washington Post)

The sunny lounge in the Upper School is a privileged spot reserved for eighth-graders to relax and hang out. Two weeks before winter break, seven of them gather during lunch.

“It kind of makes your last year special,” says Ethan Bean, leaning back on a comfortable sofa.

Nysmith ends at eighth grade because, as Carole and Ken Nysmith make plain, they are content doing what they do best. But for the kids, leaving Nysmith will mean finding new friends and new routines, and forming fresh identities. Scary stuff.

For some, it will also be their first brush with the kind of social hierarchies and snarkiness that define school for many of their peers.

“You might be a geek or really into computers, or you might be someone who’s really into the arts, but here you’re never termed as a geek or as an artsy person,” says Kirthi Kumar, an eighth-grader and aspiring biomedical engineer. “There are no cliques. At Nysmith, like, we’re all one mold.”

“I can’t tell you how many hundreds, maybe thousands, of families come to visit us, walk through the door expecting a bunch of little nerds,” Ken Nysmith says. “Well, what’s a nerd? A child who loves math, a child who loves science, a child who’s socially awkward? Well, why are they socially awkward? Because they don’t have that community of shared interests. They don’t understand why other kids in the class don’t want to talk about black holes or space and just want to talk about what other kids want to talk about. I think that’s where the sense of community here becomes absolutely critical. Certainly the more exposure you have to others like you, the more you feel normal, like you belong.”

The school’s thinking seems to be that this kind of safe haven ultimately boosts EQ, or emotional intelligence. The goal of the school’s character-education curriculum is to help students embrace and celebrate the sensitive, exceptional student while honing the social and emotional skills needed to survive high school without getting a rap as an annoying know-it-all.

Nysmith says these skills are essential. “We all know very bright, intelligent people who cannot communicate their ideas, who cannot share their emotions,” he says. “It does make for a difficult life if you cannot communicate effectively.”

For Randy Wimmer, these soft skills might be more important than a perfect grade-point average. “I’m very proud of my children, but they’re not walking Einsteins,” he says. “If a person is gifted in one area, it’s probably at the expense of something else. … Maybe my kids don’t focus on sports that much, and they’re not gonna be the next NBA or NFL stars. I’m fine with that, too. But if there is a difference, it’s when my kids find that one thing they’re really passionate about … then they really invest their time and energy into it.

“At the end of the day,” he says, “I want to make sure my kids are good people. And happy. It all comes down to looking in the mirror and being happy in their own skin.”

Glen Finland is a writer in McLean, Va., and author of “Next Stop: A Son With Autism Grows Up.” To comment on this story, email wpmagazine@ washpost.com or visit washingtonpost.com/magazine.